I like Low Tech Magazine. Not only is their website solar-powered and only available when the weather is good, they provide an interesting viewpoint on technology as a whole.

Recently, they created a thematic collection of articles called “How to Build a Low-tech Internet?”. It’s sold as a hard-copy book, but not as an EPUB. Since I’m almost exclusively reading my books digitally these days - and the articles are all available on their website, I thought I’d just create an EPUB myself.

The irony of this is not lost on me.

Getting the goods

On the Low Tech Magazine website, they have a simple Archive page with all articles that they have published. I simply found all the ones in the book and downloaded them to my local machine.

I can use wget for this task, the arguments I stole from Tyler Smith:

wget -p -k -H -nd -P chapter1 https://cool.site/some-article

This does a number of things:

- It downloads the page into the given directory (

-P | --directory-prefix) - Alongside the page, it downloads all styles/images/scripts (

-p | --page-requisites) - All assets are downloaded into a single, flat directory (

-nd | --no-directories) - Even if the assets are from different hosts (

-H | --span-hosts) - Then all links to assets are rewritten to the local path (

-k | --convert-links)

This gives me a new directory with the article in index.html, all images, styles and scripts.

Opening the local index file via the file:// protocol (just by double-clicking it) opens it in the browser.

It looks and works as if it was the online version.

This works fine for this particular website, which is mostly static content. If you want to download from a website which renders using JavaScript, you’ll need to use an actual Browser. Chrome can get you stated:

/path/to/chrome --headless --dump-dom https://www.example.com

This will print the rendered websites HTML to stdout. Downloading the assets that this page links to is left as an exercise for the reader.

Creating an EPUB

With the content downloaded, I just have to put it into an EPUB. What little knowledge I had about e-books was that they’re basically a Zip file with some HTML content inside. Surely this can’t be too hard.

I looked at some ready-made tools available on the internet. Either their output wasn’t nice enough, they were too clunky, or they did too much. It might have just been my own curiosity though.

I started off by looking at how another great online source for e-books does it: StandardEbooks They take publicly available works, digitized for the public and carefully touch them up to professional standards. They have a great catalog and a most importantly, a very detailed guide on e-book creation, typesetting and some nice tooling.

I started by looking through their extensive manual of style - and immediately decided this was too detailed. Their Step-by-step guide turned out to be a more appropriate resource. Throughout the guide, they use their own tooling to perform various tasks. Which got me thinking.

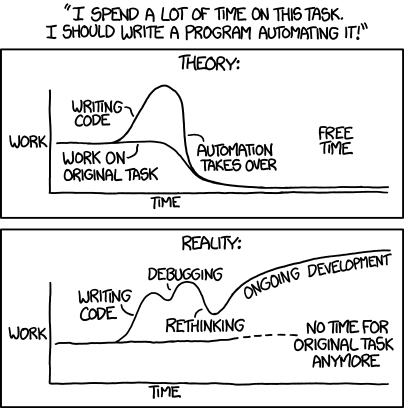

Going through the guide, it struck me that there was a bunch of manual work involved. While I was initially happy to do it once for the one book I really wanted to make, I felt an itch.

Automation

So, I want to automatically bundle a bunch of static HTML into an EPUB container. I will need to:

- EPUBs use XHTML, so I will have to convert the downloaded HTML to valid XHTML

- I only want the actual article portion of the page, so I have to extract that part

- Cleanup the XHTML and remove unnecessary elements and properties (like styling) left over from the website

- Bundle and link all the Images used in the articles

- Generate the required EPUB scaffolding like the manifest, table of contents, etc

Let’s get started.

Wrangling HTML

You wouldn’t parse HTML with Regex, so what else is there? Because I had just installed the Standard e-books tools, which are written in Python, I read into BeautifulSoup. This library can parse an entire DOM from an HTML source and offers navigation and manipulation functions.

My first attempt at a script to clean up and convert my HTML to XHTML looks like this:

import sys

from bs4 import BeautifulSoup

def cleanup(tag):

for noise in tag.find_all(["div", "section", "header"]):

noise.unwrap()

with open(sys.argv[1]) as source:

soup = BeautifulSoup(source, "html.parser")

article = soup.find("section", id="content")

cleanup(article)

with open("out.xhtml", "w") as dest:

dest.write(str(article))

I looked into the HTML files of the articles I had downloaded and found that the content was in a single <section> tag.

Next I looked for any elements that were needed on the website only and unwrapped them, removing the element and it’s properties but retaining its inner tags.

Lastly, converting the DOM to a string gives valid XHTML by default, so just write that out.

This approach has problems. For starters, the code is too specific to the HTML structure of the articles from Low Tech Magazine. It assumes too much about it’s input to be useful elsewhere.

The second issue is that now, with elements like <header> unwrapped, the title and author are just part of the article body.

This makes it hard to present them clearly.

It also makes it hard to automatically generate a table of contents from the articles without making the code even more specific to the structure.

Learn to stop worrying

By chance when looking into how other tools automate this part, I came across mozilla/readability. This is the standalone library powering the FireFox “Reader View” feature. It simplifies page content and presents it very much like an e-book reader would.

Eureka! I can harness this power for myself. It’s pretty simple too:

const { JSDOM } = require("jsdom")

const { Readability } = require("@mozilla/readability")

const fs = require("fs")

function simplify(html) {

const doc = new JSDOM(html)

const reader = new Readability(doc.window.document)

return reader.parse()

}

const file = fs.readFileSync(process.argv[2], "utf8")

const simple = simplify(file)

fs.writeFileSync("out.xhtml", simple.content, "utf8")

Since “readability” is a JavaScript library, I switched over from Python. The above code parses the entire HTML file, finds the relevant article text and simplifies it greatly.

“readability” also parses a bunch of metadata from the article, such as title, author publishing time, etc.

I could simply render this information into a <header> for the article.

But this is also exactly what I need to build a table of contents later on.

Crucially, the result still has many <div> and <span> tags used for styling.

In my pursuit of clean, simple XHTML, I will still have to find and unwrap these tags.

And while this was easy enough with BeautifulSoup, JSDom doesn’t surface a nice and simple API.

I thought about using jQuery on top of JSDom to make the API nicer, but decided this was madness.

Perspective shift

What I need is a simpler intermediate format. One that doesn’t allow for complicated markup and focuses on purely textual content. That allows me to store the extracted metadata along with the content, in a structured form. And that can easily be converted to XHTML again.

---

title: Test

author: Me

---

# Obviously

Markdown is my intermediate format! With YAML front-matter to store metadata.

The aptly named turndown library does exactly that: Turn HTML to Markdown. It does not support the YAML front-matter out-of-the-box, but that’s easy enough to add.

const TurndownService = require("turndown")

function generateMarkdown(readable) {

const td = new TurndownService()

td.keep(["table"])

return td.turndown(readable.content)

}

function generateFrontMatter(readable) {

// NOTE: Can't correctly indent this because then front-matter in the file is indented and breaks YAML

return `---

title: ${readable.title}

author: ${readable.byline}

---

`

}

// In addition to the above script

const output = generateFrontMatter(simple) + generateMarkdown(simple)

fs.writeFileSync("out.md", output, "utf8")

This gives good results. Now I have a simpler format that still retains the actual content of the article. As an added bonus, it’s much easier to make manual changes to a markdown file.

You can find the full script in the repo that accompanies this post.

Bundle to EPUB

With the actual content now cleaned up, it is time to bundle everything together.

Rather than read through the EPUB standard, I looked for a minimal working example instead. I found Minimal E-Book, which is exactly that. Let’s get the simple stuff out of the way first:

- A

.epubfile is a renamed ZIP file - In the root of that ZIP file, the

mimetypefile is located withapplication/epub+zipas it’s content - Also in the root, the standard expects a

META-INFfolder with a singlecontainer.xmlfile - That file simply points to the

content.opffile, which can exist in an arbitrary directory - The

content.opffile is a manifest of all files the e-book references

With this information, let’s build a simple bundler. It receives markdown files as arguments, renders them to XHTML and adds them to the manifest.

const { marked } = require("marked")

const { markedXhtml } = require("marked-xhtml")

const frontMatter = require("yaml-front-matter")

const Handlebars = require("handlebars")

marked.use(markedXhtml())

const articleTemplate = Handlebars.compile(fs.readFileSync("templates/article.xhtml").toString())

const manifestTemplate = Handlebars.compile(fs.readFileSync("templates/content.opf").toString())

function parseArticle(file) {

const content = fs.readFileSync(file, "utf-8")

const matter = frontMatter.safeLoadFront(content)

matter.id = path.parse(file).name // file-name without the extension

return matter

}

function writeArticle(article) {

const content = marked.parse(article.__content)

const rendered = articleTemplate({...article, content})

// TODO write the file to our ZIP file

return {file: article.id+".xhtml", id: article.id, mimetype: "application/xhtml+xml"}

}

const files = process.argv.split(2).map(parseArticle).map(writeArticle)

const manifest = manifestTemplate({files})

// TODO write manifest to ZIP file

The snippet omits writing the actual files to the file system/ZIP file for brevity. The article template is less interesting, lets look at the manifest instead:

<package xmlns="http://www.idpf.org/2007/opf" version="3.0">

<!-- Metadata element removed -->

<manifest>

{{#each files}}

<item id="{{id}}" href="{{file}}" media-type="{{mimetype}}" />

{{/each}}

</manifest>

<spine>

{{#each files}}

<itemref idref="{{id}}" />

{{/each}}

</spine>

</package>

NOTE: This snippet is shortened - and therefore not fully valid.

The main elements are:

<metadata>(we’ll look at that later)<manifest>lists all files in the EPUB<spine>sets the order in which Text files are stitched together into a book

If I Zip all of this up together, the structure should look like this:

out.epub

├── META-INF

│ └── container.xml

├── mimetype

└── OEBPS

├── c1-internet-speed-limit.xhtml

├── c2-18th-century-email.xhtml

└── content.opf

This is a valid EPUB! A boring one though.

Styles

Since EPUB builds on web technologies, it makes sense that styling is done in CSS. It also makes sense that the support varies a lot from vendor to vendor. Some styles are accepted by some readers but ignored by others.

To make it easy on myself, I reused this CSS Boilerplate and simplified it. I did add some extra rules for chapter headings, though. The full style is in the repo if you’re interested.

As this is yet another file, it also requires an entry in the <manifest> of our content.opf file.

The entry has the same format, except the mimetype is text/css.

I can then link it in the XHTML files using the normal <link href="css/style.css" rel="stylesheet" type="text/css"/> tag.

Note that the href is relative to the content.opf file, so no traversal via ../ is required.

Images

This is the more interesting problem: Images from the articles are downloaded together with the text, so the final EPUB should also have these images. In practice this means I have to:

- Find all the images referenced in an article

- Find the local image (if it exists)

- Add the image to the ZIP file and

<manifest> - Rewrite the reference in the article to match the path inside the EPUB

Luckily, the “marked” Markdown library I’m using allows invoking the lexer directly, which gives us the AST for the parsed markdown file. To explain what that means and why it helps, lets look at an example:

> marked.lexer("")

[

{

type: 'paragraph',

raw: '',

text: '',

tokens: [

{

type: 'image',

raw: '',

href: 'path/to/img.png',

title: null,

text: 'the alt text'

}

]

},

links: {}

]

For the given Markdown text, the lexer parses the syntax into a (very small) tree.

The first node in the tree is the paragraph, which wraps all markdown blocks.

Next, we have the image with the href pointing to the image file.

This is what I’m interested in.

function writeImages(tokens, article_id, zip, results) {

for (const token of tokens) {

if (token.type === "image") {

if (fs.existsSync(token.href)) {

const zip_path = `img/${article_id}/${path.basename(token.href)}`

// add to Zip

zip.file(zip_path, fs.createReadStream(token.href))

// Rewrite href

token.href = zip_path

// add to manifest

results.push({file: zip_path, id: zip_path, mimetype: mime.lookup(token.href)})

} else {

console.warn(`Image ${full_path} not found. Ignoring...`)

}

} else {

writeImages(token.tokens, article_id, zip, results)

}

}

return results

}

This simple recursive function traverses the AST, looking for any image nodes.

Once it completes, all referenced image files are in the ZIP and the href are updated to reflect the path inside the EPUB.

Doing this while bundling the e-book has the benefit that it does not matter where the images are stored on disk, as long as the references to the image files are valid.

The array I return has the same objects as the writeArticle from earlier.

I can update the function to return an array instead of a single object and add both article and its images to the manifest:

function writeArticle(article) {

const tokens = marked.lexer(article.__content)

const images = writeImages(tokens, article.id, zip, [])

const content = marked.parser(tokens)

// ... code as before

return [

{file: article.id+".xhtml", id: article.id, title: article.title, mimetype: "application/xhtml+xml"},

...images

]

}

// Replace map() with flatMap()

const files = process.argv.split(2).map(parseArticle).flatMap(writeArticle)

const manifest = manifestTemplate({files})

With this in place, I now have all files in the ZIP and listed in the manifest. Almost done!

Table of Contents

I lied to you.

In the snippet above, I snuck in an additional change.

I added title to the object describing the article.

I have this information from the metadata the “readability” library parsed out. It’s time to use it now to create the Table of Contents.

function writeManifest(zip, files) {

const toc = files.filter(f => !!f.title)

zip.file("toc.xhtml", tocTemplate({toc}))

zip.file("content.opf", manifestTemplate({files, toc}))

}

I use the title property to filter out everything that should show up in our table of contents.

The actual table is created using the toc.xhtml file, which is pretty boring again (it’s just an <ol>).

More importantly, I have to update content.opf with this new information:

<package xmlns="http://www.idpf.org/2007/opf" version="3.0">

<!-- Metadata element removed -->

<manifest>

<item id="toc" href="toc.xhtml" media-type="application/xhtml+xml" properties="nav" />

<item id="style" href="css/style.css" media-type="text/css" />

{{#each files}}

<item id="{{id}}" href="{{file}}" media-type="{{mimetype}}" />

{{/each}}

</manifest>

<spine>

<itemref idref="toc" />

{{#each toc}}

<itemref idref="{{id}}" />

{{/each}}

</spine>

</package>

I updated <spine> to only include the table of content files.

If I didn’t do that, the CSS file and all our images are in the <spine> as well.

Note that the toc.xhtml entries are static, because they’ll always be there.

Now there is an automatically generated Table of Contents from our actual article titles. Everything is coming together nicely.

Metadata

Last stop: metadata.

I have held onto this bit for last because it’s more involved than is apparent.

Here is the content.opf file again, this time only the <metadata> part:

<package xmlns="http://www.idpf.org/2007/opf" unique-identifier="uid" version="3.0">

<metadata xmlns:dc="http://purl.org/dc/elements/1.1/">

<dc:identifier id="uid">urn:uuid:{{uuid}}</dc:identifier>

<dc:title id="t1">{{title}}</dc:title>

<dc:creator id="author">{{author}}</dc:creator>

<dc:language>en</dc:language>

</metadata>

<!-- manifest/spine come here -->

</package>

The EPUB 3.3 specification defines the required meta elements are dc:identifier, dc:title and dc:language.

While title and language are pretty clear, the identifier is supposed to identify this particular book uniquely.

It is referenced in the <package> element, where unique-identifier points to the ID we gave to the dc:identifier element.

Because my bootleg book doesn’t have an official ISBN, I use urn:uuid and generate a new UUID each time its bundled.

Note that the spec says:

Unique Identifiers should have maximal persistence both for referencing and distribution purposes. EPUB creators should not issue new identifiers when making minor revisions such as updating metadata, fixing errata, or making similar minor changes.

So if you’re going to publish the EPUB, the identifier should be more stable than this. For my purposes, where I’m just building them for myself, it’s fine though.

To verify the book - including the metadata - I use EPUBCheck.

You can freely download it and let it run over the whole .epub file.

It was helpful to point me to articles that required additional manual touch up.

Wrap up

That’s it. Did I have to make it this complicated for myself? Probably not. It was a rewarding little programming exercise that I could work through without major hurdles and just build out. It was fun. And now I have a new book to read.

The snippets in this article are taken from the accompanying repository, which has the full scripts, template and docs.